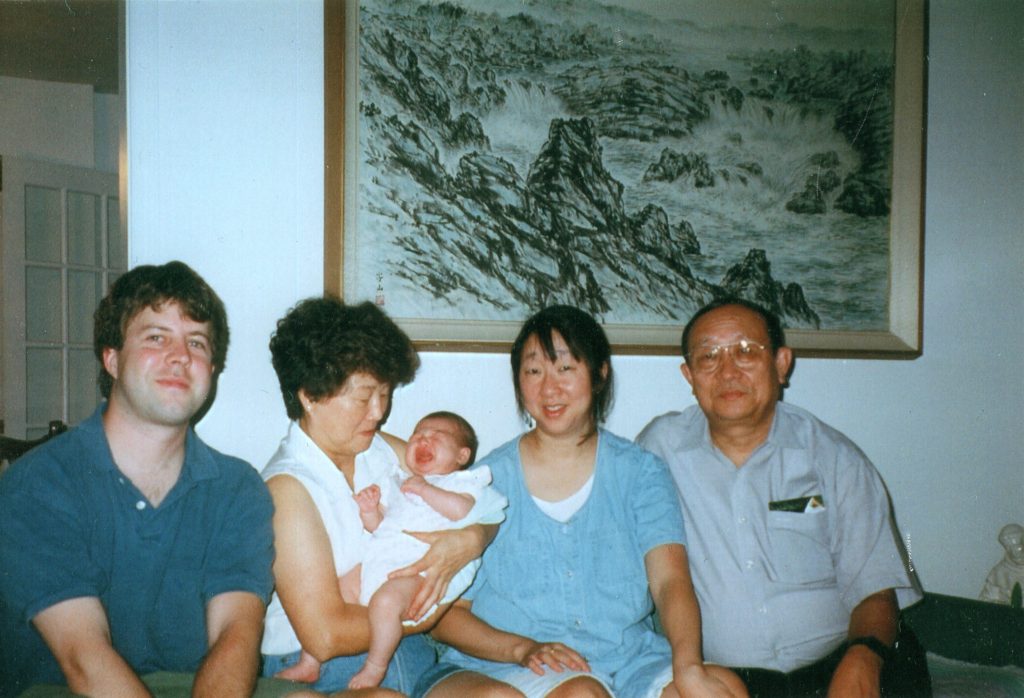

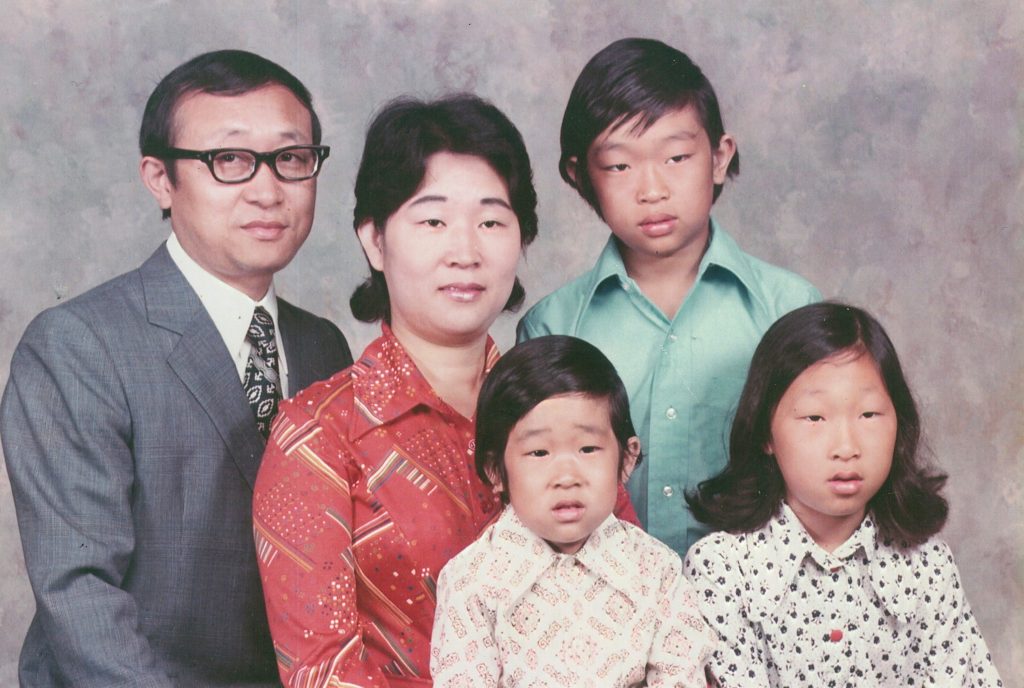

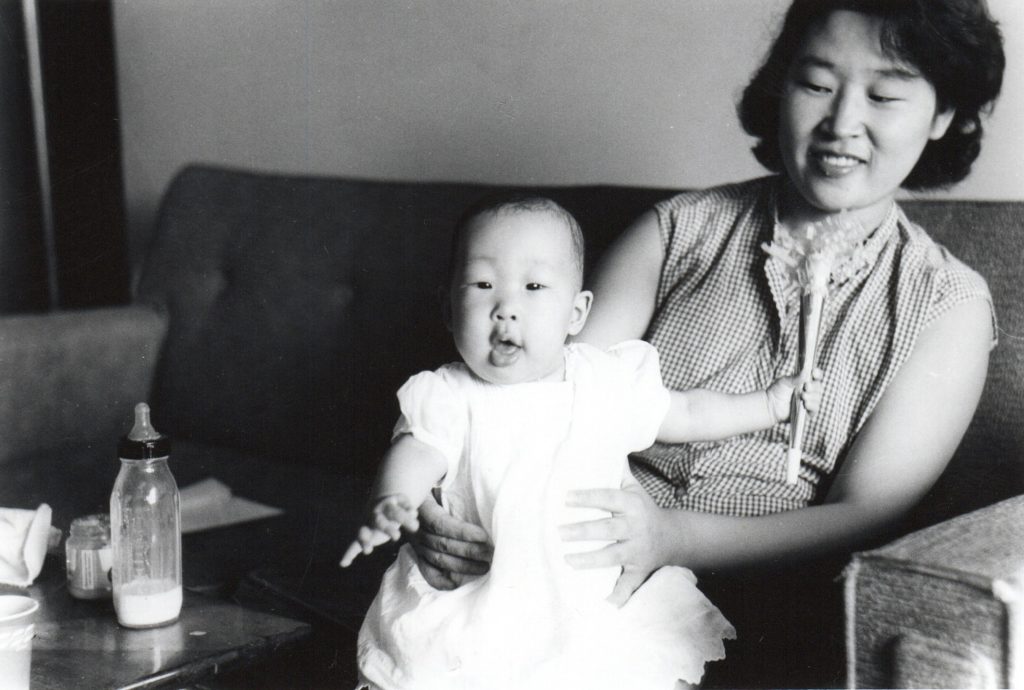

Carol Sunai Lim is Henry and Sunny’s daughter. She is married to Thomas, and mother to Natalie and Lanie.

When asked to write something about my mom, her strength, determination, creativity, and fierce loyalty to family come to mind. You may not know that my mom was an athlete in high school—a track star. I also remember seeing a painting that she had made (green and blue; can’t remember the details) that was quite good. And she had a great love of the violin. Despite my mom’s late start on the violin, she studied at the New England Conservatory. She eventually had a long career teaching violin, starting with my 4 year-old brother Mike. She also tried to make violinists out of me and David, but we were not quite as talented as Mike! We all played 2 instruments at some point in our lives. My mom was a proud member of the Lafayette Symphony Orchestra, and we saw so many concerts; “Peter and the Wolf” is burned into my brain, as well as all the Suzuki songs we heard every day when she taught violin. She went on to become a highly successful violin teacher, at one point having more students making it to All-State Orchestra than any other teacher in Southern California.

My mom pushed all of us children to succeed—she was really the main driving force in our family for everyone, including my dad as she pushed him to get a PhD to advance his career. She pulled many “tiger mom” maneuvers to get her kids into the best situations, including bursting into the famous violinist Josef Gingold’s office at Indiana University and had Mike play for him, and take him as his student. She also thought that all of her children should get advanced degrees, and we did that. I was glad to be able to tell her before she passed away, that I am who I am today because of her. Her “brainwashing me” starting as a 5 year old—“never become just a housewife—do something else with your life” and pushing me to leave my job as a pharmacist to go to grad school (“my daughter works at Walgreens” was used to shame me to move on). To give my mom credit here in writing, to boast about her many accomplishments, is something she would have loved, as she lived in the shadow of my dad who seemed larger than life. My mom and I had difficulties for years, as I viewed her “advice” as bossy and controlling, but during the last 10-15 years, I understood her better. I resisted her “advice” almost every step of the way, but I did become what she wanted me to be—married with 2 kids, a professor, and I found God, which was really important to her. And during the pandemic, everything softened, and we got along so well. So as she in the hospital, ill from COVID, all of that “controlling” she was doing in the past just looked like so much love to me, something I didn’t see for most of my life. She loved my children more than anything else in the world… I feel the most sad for them.

One of her last conversations with me, she was so proud of me for getting 2 NIH grants and being promoted to Associate Dean. She loved hearing about how much money I would make, and she stated, “it’s good to have a job where you tell other people what to do.” In some senses, I think she felt that was her job her entire life.

Now there will be no more packages sent from her, of surgical masks, Dial soap, hand sanitizer, gloves, Vienna sausages, the best seaweed from Korea (only available at the Seoul airport), Slo-Mag tablets, Korean cookies, sesame candy, winter coats, designer handbags, packages of white socks from Walgreens, cashmere sweaters, and $200 Lancome or Estee Lauder face creams… There will be no more cards/checks sent to us for any occasion they could think of—birthdays, anniversaries, getting straight A’s, getting promotions, valentine’s day, get well cards when we were sick.

Lastly, there will be no more phone calls or messages with her saying, “Carol, this is mom…”

My dad was my role model for as long as I could remember. He was extroverted and gregarious, well-liked by others, and a professor. Everything about his job seemed fascinating to me. I would go with him into his lab in the summers, and he even would have me count the number of words in the manuscripts he had written (back then for some journals, you got paid per word). He had scores of graduate students who adored him not only for his intelligence, but for his warm and caring personality. He made it look fun to be a professor. He told us countless stories of his workplace, from hiring new students from Korea, to difficulties being a foreigner (and fighting for equal pay/rights early on as a professor). He was an award-winning teacher, and regaled us with stories, like how he would write on the chalkboard starting with his left hand, then transferred the chalk to the right hand to continue (he was a lefty but his father made him write with his right hand in childhood). My dad was a peacemaker—while at Purdue there was a big conflict between the Korean and Japanese students (due to past history of occupation, wars, etc.), but my dad served as a mediator to smooth things out. There was a newspaper article on his mediation years ago. My dad told of us of the occupation of Korea by Japan, had to change his name (temporarily), but never harbored ill will towards the Japanese. In fact, my parents had close Japanese friends while in Indiana.

My dad integrated us into academic life. My parents were famous for hosting picnics with grad students, inviting students and visiting scholars over to our house for dinner, entertaining over holidays. The life of a scientist requires dedication to work, and did not allow for much time to make friends outside of work—so my dad made friends with those he worked with. Graduate students are only with you for 4-6 years, so I’m sure it was difficult to see them leave—but with most he maintained lifetime relationships.

It wasn’t until high school that it was apparent that I had an inclination for science (chemistry in particular). But my entire life, my dad made me believe I could do anything—and my mom made me believe I had to do something important. It was almost my fate to become a scientist, as I greatly enjoyed studying and thinking. As a 17-year old I had journaled about my future career, and I had already decided then that I wanted to become a professor like my dad. My parents had crushingly high standards, but also gave me full support during my pursuit of becoming a professor. My dad was even able to help me with calculus in college (albeit with some impatience). I think in part I became a scientist to make my parents proud of me. But when I landed my first tenure-track faculty position, I wondered, “did I do this for them, or for me?” Then I realized it didn’t matter. What I did for them was for me. During my time as a faculty member, I sought out my dad’s advice on how to navigate academia—being an Asian female faculty member in Utah was maybe not unlike my dad’s experience of being a minority faculty member in Indiana. He always gave me sound advice, and taught me how to fight battles with strength, calm, and grace. He taught me to negotiate for higher pay, how to deal with difficult faculty members, advised against being too emotional with administrators, and how to resolve conflicts. He also taught me how to write good rejection letters (as I have served as chair of many of our faculty search committees)—stating “while you have excellent qualifications and experience, our department chose another candidate due to a better fit” or something to that effect. I found that once I started writing rejection letters like that, candidates would often respond back with a thank you and other niceties.

Late in life, my dad found religion, and the end result was that, although he was a skeptic on some things, he lost all of the anger he had from the past. That’s when I realized it was real for him. “But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control” (Galationas 5:22-23). Many of these my dad already had; some were being worked on, but God revealed many of these to my dad’s heart.

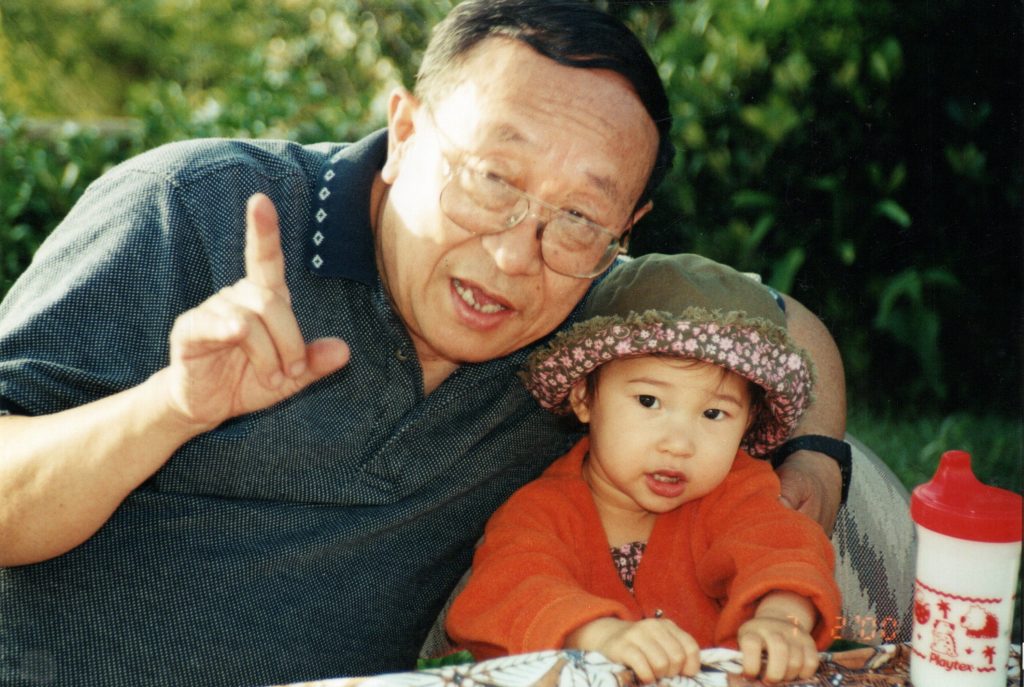

When I had children, my parents switched into this mode of “super grandparents.” It became clear that grandkids were the most special thing to them. My kids were showered with love, affection, gifts, cards, money, and visits on their birthdays. It was somewhat overwhelming to my kids, but they were the most adoring grandparents anyone could ask for. My parents loved hearing about my kids’ accomplishments—from Natalie being a “mathlete” in elementary school, getting excellent grades, singing and acting in school plays, artistic ability and art awards, helping her friends in need, to Lanie’s straight A’s, perfect ACT score, making varsity lacrosse, and going to nationals for debate—my parents drank it up and reveled in their accomplishments, which were made possible by my mom crossing the border of North Korea/getting shot at; both my mom and dad excelling in school which brought them to the U.S. where they met. Their lives made ours possible, which made my kids’ lives possible. I think they longed to see what opportunities we kids might have, and hoped that the next generation (my kids) would do even better. They were so proud of us, especially my kids, the light of their lives.